Most companies have already been through a first phase of driving cost efficiency in their IT infrastructure, taking measures such as consolidating into fewer (or one) global data centres, and outsourcing infrastructure operations. However – according to the hype, at least – The Cloud (or infrastructure as a service, IaaS) promises to offer a whole new wave of cost reductions, efficiency savings, and service improvements, but probe just a little deeper, and some big questions quickly become apparent.

- What is really meant by ‘Cloud services’ in this sense? Every supplier seems to use the term, but do they all mean the same?

- Enabling both cost savings and service improvements sounds like ‘having the cake and eating it’ – surely too good to be true?

- What suppliers should we turn to for help? Are our established IT suppliers (and/or infrastructure outsourcers) best placed, or does the brave new world of the Cloud imply new and different suppliers?

- What are the big challenges and risks in doing this?

- And – probably the biggest question of all – are these types of Cloud services really ready for the big time? By which we mean not just for supporting the odd web site – but for big, mission-critical, transactional systems (e.g. ERP) for top tier, global, blue-chip companies .

We have worked with two clients – one a FTSE 250 manufacturer, one a FTSE 250 consumer goods company, both global brands and household names – on pioneering programmes to move their data centres to the Cloud. Based on that experience, this paper explores some practical answers to those big questions.

What do we really mean by Cloud in this sense?

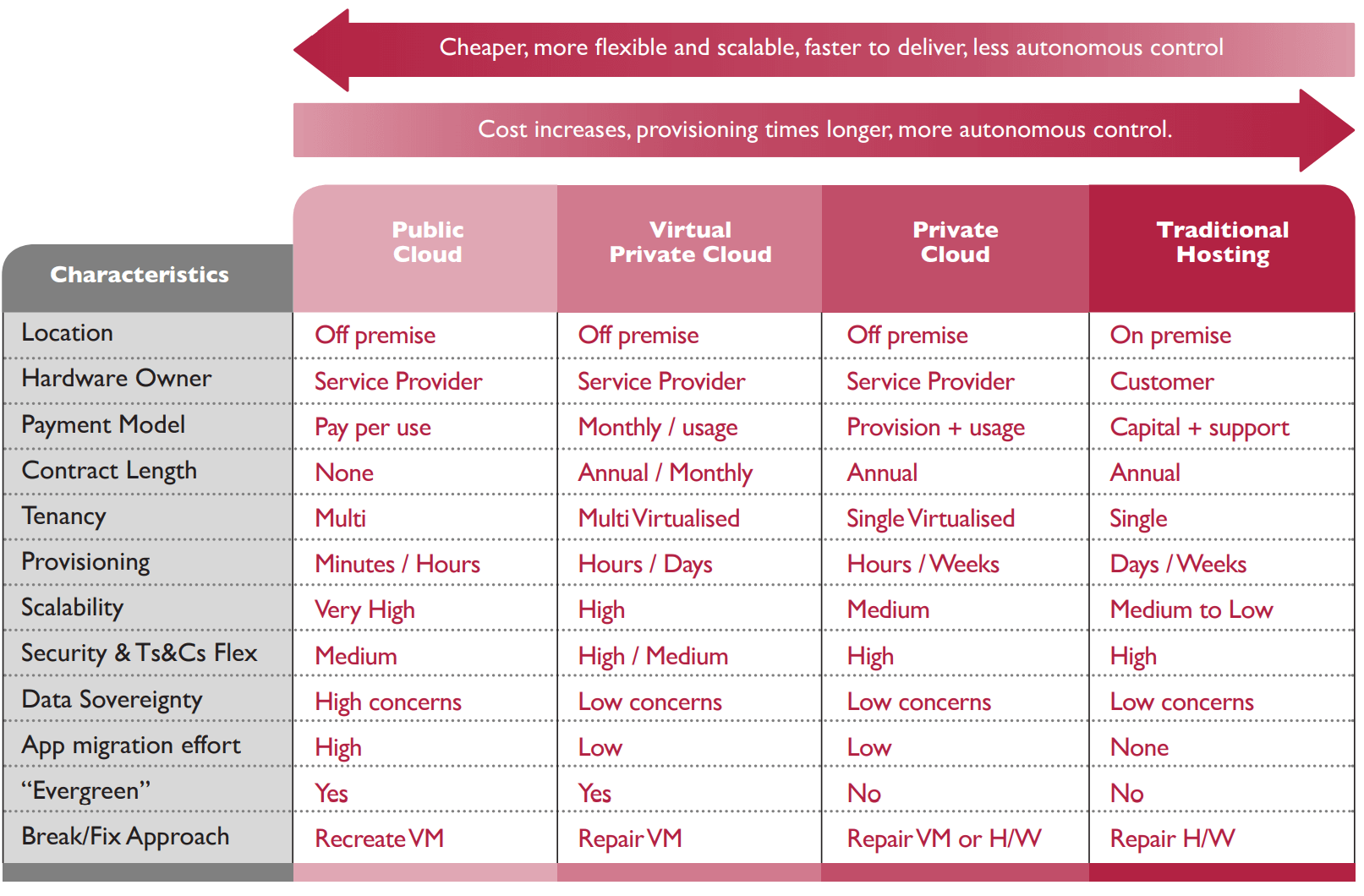

Cloud is one of those terms, like Big Data, that has become so frequently used and hyped that you will see the terminology used – whether justifiably or not – to describe a very wide range of services. For the sake of IT Infrastructure as a Service (data centre services), we use the model and terminology as shown in the table below.

So the first key point to note is that when you go out to market to procure Cloud services, you may get a wide range of responses in any one of those four categories described below, or they may have characteristics that span more than one category. Typically, the ‘industrial strength’ offerings that are suitable for big, mission critical, transactional applications are the middle two – with Virtual Private Cloud arguably offering the most promising ‘best of both worlds’ combination, many of the cost and agility benefits of public cloud, but with the control, tailoring, security and risk-mitigation benefits of traditional hosting.

We don’t currently see public cloud (most famously Amazon Web Services) as being the preferred option for these sort of industrial strength corporate applications – other corporate uses certainly, but ready to host the ‘big iron’ transactional ERP systems of some of the world’s largest companies? Probably not yet – but it’ll be interesting to see how the space develops.

We’ve helped one of the world’s largest energy companies move the entirety of their external web site hosting to the public cloud and a major automotive manufacturer put their SAP CRM instance on public cloud (with a third party service wrapper). But we haven’t yet seen anyone put true, ‘backbone’ transactional ERP on public cloud.

What flavour of Cloud do I want?

In determining which of these models is best for you the key, as ever, is to understand what your needs are, i.e. what characteristics of the service really matter for you? These characteristics tend to fall into two groups:

Some key commercial characteristics:

A Cloud service should really offer utility pricing, i.e. a true pay-as-you-go service, with zero fixed costs, which can be scaled up and down (by compute power, by storage volume, by number and type of Virtual Machine, etc.) as much as you like – which is clearly the most beneficial model in terms of flexibility. However, typical commercial offerings in the Virtual Private Cloud or Private Cloud space do not offer 100% utility pricing. For example, there might be a ceiling or a floor to the scale down / up, and/or some fixed or base costs in addition to the variable component. So it is important to probe just how close to a real utility model each offering is.

A pure Cloud service should mean you don’t own any of the IT hardware assets; and nor should you pay for their refresh and replacement. Some so-called ‘Cloud’ offerings (particularly those badged as Private Cloud) will still require hardware to be specifically purchased and built for you, and will still expect you to pay for their refresh (however that may be hidden or obfuscated in the commercial arrangements) when they come to end of life. So you need to look for a truly ‘evergreen service’ where it will stay up to date with no component of the pricing that is linked to hardware refresh cycles.

This is an area often overlooked by people more interested in the technology, but the legal / contractual aspects of committing to a Cloud service are actually an important area of differentiation. A public cloud service is rigid in this respect – the T&Cs will be fixed and common (either ‘Click to accept’ or walk away) and, of course, favourable to the supplier.

For most big companies considering mission critical applications, that’s simply not going to work – you need to be able to tailor the contract (for example, in terms of warranties and liabilities, SLAs, service credits) to be fit for purpose. However any ‘real’ Cloud service is to some extent shared, so there are some Ts&Cs where it is reasonable to expect the supplier not to budge (because they are inherent to offering a shared service, and simply cannot be different for each customer for genuine and practical reasons), but there are others where they can and should be possible to tailor. Again, it is important to explore this before committing.

Some key technology and service characteristics:

The scope of a typical Cloud service in what respect is usually IT infrastructure (computer, storage, networks), including all the necessary backup, service resilience, and disaster recovery contingencies; and software support only up to the OS, database and SAP Basis layers of the stack. A range of other services (e.g. Application Management) may be offered, but this will typically be a bespoke offer, and should be treated much like buying any other traditional IT outsourcing; so it is really a separate quantity from buying the core Cloud service.

A pure Cloud service will use virtual machine (VM) technology and shared storage such that none of the physical hardware will be specific to you; it will be shared with other customers of the service, like multiple people sharing the same house (hence the term ‘multi-tenanted’). But clearly, in this case, you need to ensure that your data and compute power (your ‘room within the house’) is sufficiently secure and isolated from any potential impact of other tenants.

It also may not be suitable for everything you want to put in the Cloud; when the size of any one virtual machine becomes more than a certain percentage of the capacity of the underlying physical hardware, the overheads of virtualisation outweigh the benefits and you may be better off, as Olivia Newton John once put it, getting physical. Hence service providers will generally have a size / capacity limit for what is ‘certified’ to run on their multi-tenanted Cloud platform – and that big SAP database server you have, for example, might not fit.

The VM platforms will typically only come in a few fixed varieties, as well (e.g. Windows and one or more flavours of Linux; and not all database platforms may be supported). Finally, some older technologies and applications might not be suitable for virtualisation anyway (or not without a lot of expensive re-work) – especially for public cloud where applications have to be fully engineered for ‘disposability’ (you never repair; just throw away and re-create). So it is important to understand what will be virtualised and physical (and multi- versus single- tenanted), and what the implications of that are.

For a pure Cloud offering, as for the technology, much of the service operations will be a shared service as well. But again, many of the Virtual Private Cloud and Private Cloud offerings will enable you to tailor this – such that you have bespoke service levels, or bespoke support arrangements (for example, you might want a dedicated, in-country, local-language-speaking, service manager in certain key locations across Americas, Europe and Asia).

But varying from ‘the standard and shared offer’ may have cost, scale, longevity and flexibility penalties – some of which may not be evident from the outset. In their enthusiasm to sell / offer the exact service that you want to buy, a supplier may offer non-standard arrangements without making it clear that’s what they’re doing. It may be the right thing to do, but you should at least encourage your supplier to make it clear what their standard offer is, and when they are proposing something that varies from it, so that you can make that conscious choice.

Where your data is physically stored, and therefore what legal and regulatory regime applies in terms of data protection and management, is another key consideration. Perversely, the United States – highly fiscally and politically stable, and with world-leading technology skills – may be one of the least attractive countries due to the implications of their Patriot Act legislation. So you may need to balance that against the cost attractiveness of the Far East, and the political and legislative attractions of Europe (where Eastern Europe may still offer some, if not perhaps all, of the cost benefits of the Far East).

Both cost savings AND service improvements…. really?!

This may sound like both having your cake and eating it, and we were originally sceptical that both could be achieved. But the reality is that for a well run and well implemented Cloud service, the pure economies of scale mean that it should be able to offer a better service for a lower cost. But obviously, the big caveat here is that it all depends on your starting point (in terms of how cost effective, and how good a service, your previous IT infrastructure operational arrangements offered).

In our practical experience of migrating the entirety of a global datacentre for a FTSE 250 manufacturer (both SAP and all non-SAP, Windows and Unix), the transition will have achieved:

- Total operational cost savings (on a cash basis) of 42%

- Service level improvements – most key SLA metrics (for availability, incident and change management, etc.) were better than previously, and the remainder were the same (i.e. none were worse, and the net position was certainly an improvement)

- Flexibility – a largely (but not completely) utility-based pricing approach, with a 50% capacity floor, means there is ample room for major service changes (e.g. to support corporate acquisitions and divestments) with the commercial model flexing on demand, and little risk of being left over-or under-capacity

- Responsiveness – the time to stand up new environments (e.g. new development and test environments for projects) will go from a matter of weeks to a matter of days (albeit still not hours / seconds like public cloud would be; but that is simply not a requirement for this particular client)

- Security – having done extensive review and analysis, the client’s internal IT security experts considered the Cloud service to offer the same or better IT security overall than the provisions under their previous hosting arrangements – despite the multi-tenanted approach. Importantly, the contractual recourse (i.e. warranties, indemnities and limits of liability) in case of security breaches is also better than their previous arrangements.

Which suppliers should I turn to?

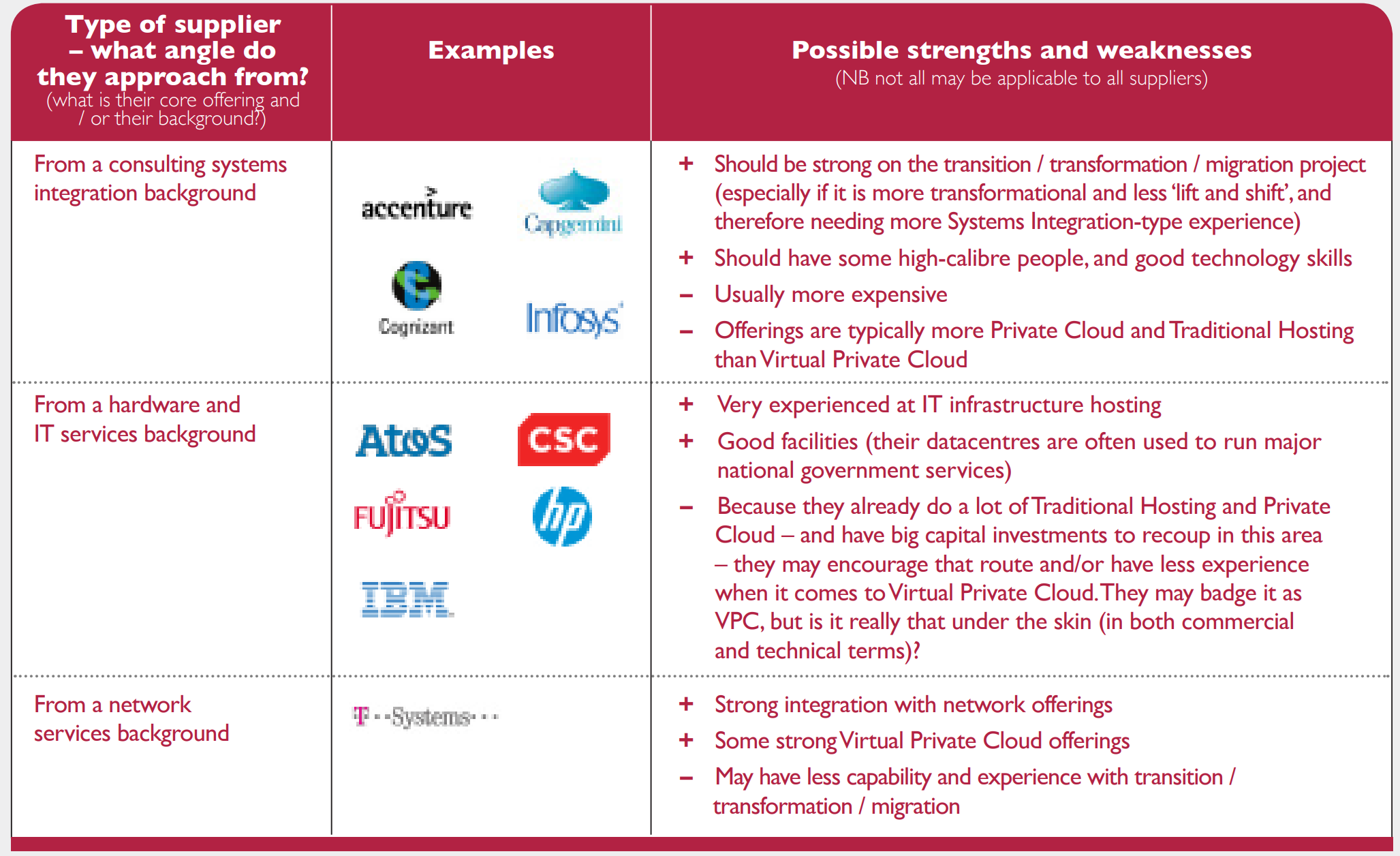

The suppliers of these types of Non-Public Cloud Services generally fall into three groups, each of which has strengths and weaknesses as shown below (although we risk some unfair generalisation in this list – clearly, each specific supplier will have their own strengths and weaknesses).

We would recommend including a range of suppliers across those categories to respond to your RFP / RFI, so you can see the full extent of the services on offer. You may also want to consider whether you want the same partner for the transition and transformation work as the hosting, or whether different partners offer the best approach. See the ‘One throat to Choke’ discussion below!

What are the big challenges and risks?

Again, it’s worth considering both the commercial risks and also the technology and service risks. Although this is by no means an exhaustive list, some of the common themes (in our experience) of risks and challenges we see across clients in this area are as follows:

This is clearly a key area to get right. Even for Virtual Private Cloud, don’t be fobbed off with a ‘one size fits all’ approach. Yes, there are some aspects of service levels that will be dictated by an inherently shared service (e.g. the technical design of the shared platform and its resilience features will largely dictate the availability offered), but there are many others where this doesn’t necessarily apply (e.g. incident response time SLAs). In particular, your recourse in terms of repeat service failures should be robust, and you should ensure that the Total Value at Risk (as a percentage of total monthly fees) is competitive. This is one area where outside expertise can really help. Finally, the definition of ‘available’ needs attention (it needs to be something that really means useable – as opposed to technically available but unusable!).

Warranties, indemnities and liabilities are always key areas, given this service will be running your mission-critical, transactional IT systems. You need to ensure you have protection commensurate with the business disruption that would be caused by a significant service failure or security breach (which, although hopefully very unlikely, could also have very big implications if it were to occur). Some HR matters such as subcontracting and any possible TUPE implications (at entry or exit of the agreement) may also need careful thought. Finally, the definition of when persistent service level failures constitute material breach of the contract always tends to be a contentious area. Overall, it is easy to underestimate both the time and the effort required to complete the process to select your suppliers and contract with them – and investing enough time and effort to do it well is crucial.

As above, you need to think carefully about whether the service really is based on utility pricing, and what the implications of any fixed, floor or ceiling components of the pricing are. Given the world of Cloud technology and services is changing fast, you also need to think about how you will benchmark the prices to ensure they remain market relevant over the period of the contract (which may be 3 - 5 years); in our experience, some suppliers will absolutely refuse any independent benchmarking of their prices over the contract term (due to fixed internal policies), but some will allow it – and that may be an important differentiator.

This needs to be handled just like any other IT transformation project, so the same thought needs to be applied to setup and run the project correctly (from all perspectives: commercials, technology and project management). Again, outside expertise may be required here. We’d recommend pushing for outcomes-based pricing (i.e. Fixed Price, not Time and Materials) with milestone-based payments, but this depends on both parties collaborating on a robust and thorough planning and due-diligence process prior to contract signature. The degree of ‘lift and shift’ versus ‘transform’ needs careful thought and planning (see Technology risks below).

Selecting the same To Be supplier as your incumbent IT hosting partner; and/or the same transformation supplier as hosting supplier, has the clear attraction of ‘one throat to choke’ (avoiding any risk of multiple suppliers blaming each other for project or service failures). But the benefits of multiple suppliers who are each the best in their own area may outweigh this – they did in both the examples of the clients we recently worked with on this. A key factor in this decision is, again, the degree of ‘lift and shift’ versus ‘transformation’ implied in the transition.

The cloud-style service model may imply some bigger changes for your internal IT team than are first realised. For example the operating model for application management (AM) may need to change, and/or the boundary between AM and IM (infrastructure management) may need to change. You are likely to find your skill requirements shift more towards supplier management (building a good relationship and getting great service from the Cloud service provider) than some of the technology skills that had greater prominence before. This may need careful change management – in the human, not technology sense! – to land successfully.

Moving to a VPC platform can have some significant implications for the way that major software products (such as Oracle and SAP) are licensed. Because VPC is a relatively new approach, the software licensing implications are generally not very well understood or defined. You may well find it hard to establish a clear position, even from the vendors themselves – who are often trying to sell their own Cloud and Software-as-a-Service options, which does not necessarily incentivise them to clarify the arrangements for running on other Cloud or VPC platforms (or to make those options commercially attractive).

As a starting point, it is important to look carefully at your current licensing arrangements – you may find the wording of the terms is broad enough that you can transform to a VPC arrangement and still be covered. If in any doubt, this is an area where it’s important to seek expert independent advice.

A pure ‘lift and shift’ of applications that already run on virtual platforms should be relatively low risk. But the risk profile is much higher where there is any transformation involved in the transition, which is typically under one of the following situations:

- Applications which currently sit on non- virtualised platforms

- Applications which currently run on legacy OS platforms

- Applications which will be migrated to a new Database platform as part of the transition

- Applications which currently run on proprietary Unix (e.g. HP-UX), and will be transformed to run on an open-source Linux platform (there may be proprietary / native OS calls in the application that fail unless remedial work is done)

- Applications will be upgraded in some way during the transition (e.g. newer versions of base software, or Unicode migrations for SAP specifically).

Note that these are not necessarily bad things to do – they might be necessary and/or justified. But they will all increase risk, and so our advice would be to avoid them if possible (i.e. unless they really are strictly necessary and/or properly justified). And if you do undertake them, make sure that the risks are recognised; that the transformation activities required (particularly testing) are properly planned; and that the appropriate contingencies (in terms of effort, costs, and timeline) are built in to mitigate the risk.

Overall – is it ready for the big time?

Our view would be an unequivocal (although still cautious) ‘yes’. There are now a number of case studies of where this has been done at large scale, for major global companies, and for their most mission-critical transactional applications – so it is still advanced, certainly, but no longer ‘bleeding edge’. And the benefits of very material operational cost savings (approaching 50%) and gaining some worthwhile service level improvements are simply too good to ignore. So our view would be unquestionably that if CIOs are not exploring this already, then they should be – and will be soon.